Recentemente è stata pubblica una ricerca che mostra una tecnica di tracciamento utilizzata da grandi attori del settore tech, come Meta e Yandex, che abusa una funzionalità di rete per collegare l’attività di navigazione web (anche da browser anonimi) all’identità dell’utente.

Non solo questa tecnica elude la “Cookie Law” – quella normativa europea che dovrebbe imporre un opt-in esplicito per raccogliere la volontà di essere tracciati – ma è anche difficilmente aggirabile con le comuni pratiche di protezione della privacy poiché questo metodo di tracciamento elude l’isolamento tra processi (partizionamento, sandboxing) e rende inutile anche la cancellazione esplicita dello stato (cookie, vari storage, ecc) lato client.

Come funziona?

Il meccanismo alla base di “Local Mess” è ingegnoso nella sua semplicità. Applicazioni Android ufficiali, come quelle di Facebook, Instagram o Yandex, una volta installate sul dispositivo, si mettono in ascolto su porte di rete locali usando l’interfaccia di loopback (127.0.0.1).

Parallelamente, quando l’utente visita un sito web che integra specifici script di tracciamento (come il Meta Pixel o Yandex Metrica), questi script inviano metadati della sessione di navigazione, cookie e persino comandi direttamente alle porte in ascolto sull’interfaccia di loopback.

L’app, quindi, riceve queste informazioni riuscendo così a collegare l’attività di navigazione web, che potrebbe altrimenti apparire anonima, all’identità associata all’account dell’app.

Questo permette di de-anonimizzare l’utente, superando difese comuni come la cancellazione dei cookie del browser, l’utilizzo della modalità di navigazione in incognito, vpn, ecc.

Dal punto di vista dei permessi Android, la situazione è particolarmente interessante. Non è richiesto alcun permesso speciale o invasivo per implementare questa tecnica. La semplice autorizzazione INTERNET, che la stragrande maggioranza delle app richiede per funzionare (per accedere a contenuti online, API, ecc.), è sufficiente per consentire a un’applicazione di aprire una socket in ascolto sull’interfaccia di loopback.

Ciò significa che l’utente, concedendo un permesso apparentemente innocuo e ubiquitario, sta inconsapevolmente abilitando questo potenziale canale di comunicazione locale tra il browser (e quindi la sua attività sul web) e le app installate.

Su iOS la ricerca è ancora a uno stato primordiale ma, tecnicamente, è possibile utilizzare lo stesso vettore. Così come potrebbe essere utilizzato in dispositivi diversi come Smart TV, eBook Reader, ecc, i quali non sono stati ancora indagati.

Spie

Le evidenze raccolte durante la ricerca, mostrano che non si tratta solo di un tecnicismo per il tracciamento ma è a tutti gli effetti una pratica “illecita” e nascosta che avviene senza avvertire l’utente e ovviamente senza raccogliere il suo consenso.

È palese che tali pratiche violino sia il GDPR che le policy degli Store dei dispositivi.

Infatti, il 3 giugno 2025, Facebook ha rimosso dalla libreria di Meta Pixel le funzionalità che sfruttano questa tecnica. Esattamente il giorno dopo la pubblicazione della ricerca!

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

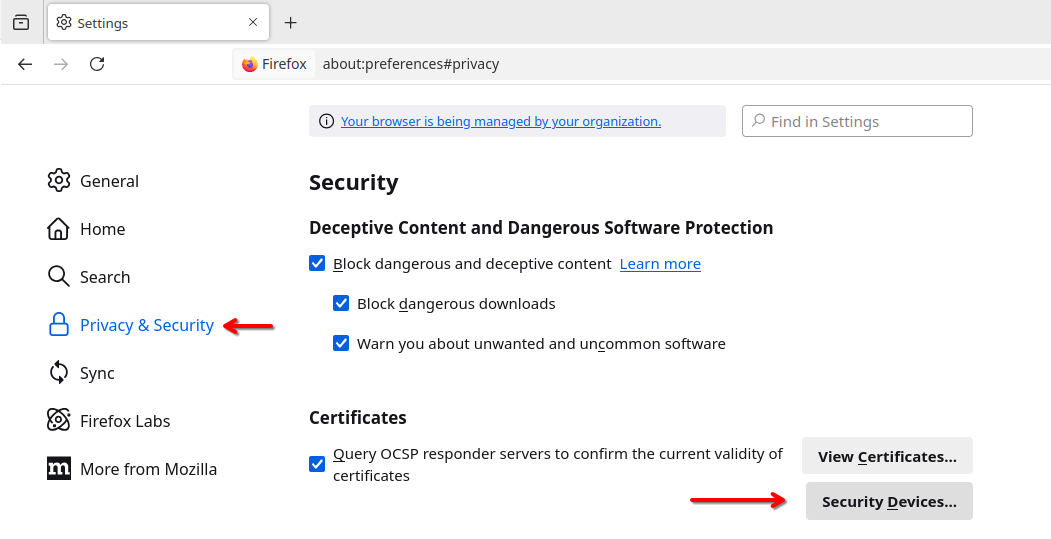

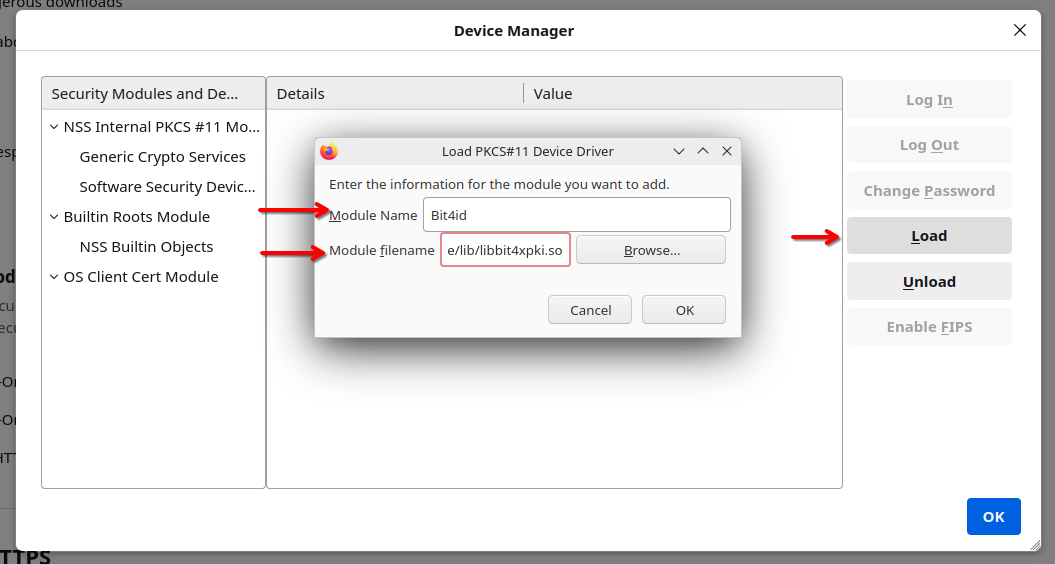

Browser e mitigazioni

Per quanto non sia un fan di Brave e non ami le sue politiche, è risultato l’unico browser non sfruttabile da questa tecnica poiché le connessioni verso 127.0.0.1 richiedono un permesso esplicito (dal 2022).

Su DuckDuckGo è possibile includere 127.0.0.1 e localhost in blocklist.

Chrome, dalla versione 137 rilasciata il 26 maggio 2025, blocca le connessioni originate da Yandex e Meta. In futuro, l’adozione di un permesso esplicito sulle connessioni a localhost risolverebbe in maniera definitiva il problema.

La mitigazione su Firefox è work in progress.

Microsoft Edge non pervenuto.

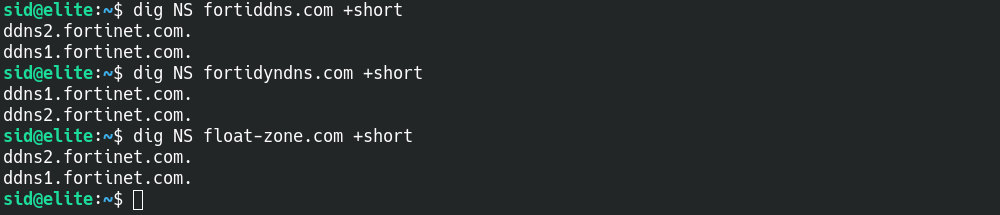

Come mitigazione generale in ambito OpSec, è buona norma utilizzare una propria VPN (non parlo di servizi come N*rd VPN e simili) per accedere ad internet dai propri dispositivi ed utilizzare dei DNS propri che implementino una blocklist, ad esempio Pi-hole.

Meglio ancora, utilizzare come forwarder di Pi-hole dei propri resolver ricorsivi, ad esempio con unbound.

Questa contromisura, nonostante non impedisca al browser di connettersi a socket aperti in localhost, bloccherebbe la libreria JavaScript di tracciamento (come Meta Pixel e Yandex) prima che venga caricata ed eseguita dal browser.

Implicazioni sulle operazioni Offensive

Se da un lato la finalità primaria descritta è quella del tracciamento pubblicitario e dell’analisi del comportamento utente, le implicazioni di una simile architettura non si fermano qui e aprono scenari anche in ambito di operazioni offensive malevole.

Una applicazione malevola, anch’essa dotata del solo permesso INTERNET, potrebbe teoricamente tentare di “ascoltare” su queste stesse porte locali, intercettando il traffico destinato alle app legittime e/o scambiando dati con gli script web.

Inoltre, è stato già sollevato da tempo come socket in ascolto su indirizzamento locale possono essere abusati per fare data leakage o persistent tracking.