Impatto sulla sicurezza relativo all’utilizzo di TLS con i servizi di Dynamic DNS (DDNS) proprietari dei vendor.

I published the original advisory, in English, @ USH – a beautiful place.

Scenario di rischio

L’utilizzo dei servizi Dynamic DNS (DDNS) integrati nelle appliance, ovvero quelli messi a disposizione direttamente dai produttori come Fortinet o QNAP, comporta un impatto sulla sicurezza in quanto il loro utilizzo si ripercuote su una maggiore superficie di attacco identificabile da un attaccante.

Attraverso questa breve analisi, si intende dimostrare come l’implementazione di tale servizio su una rete influisca sulla sua sicurezza creando un’opportunità per un attaccante di sfruttare eventuali vulnerabilità.

Introduzione a TLS e Certificate Transparency Log

La sicurezza delle comunicazioni su Internet è essenziale per garantire la confidenzialità e l’integrità delle informazioni scambiate tra utenti e siti web.

Uno strumento fondamentale per implementare questa sicurezza è rappresentato dai certificati X.509 e dal protocollo TLS, tecnologie che consentono di stabilire connessioni crittografate e autenticate.

Il Certificate Transparency (CT) è un meccanismo progettato per migliorare la sicurezza e la trasparenza nell’emissione dei certificati SSL, consentendo a terze parti di monitorare e verificare il processo di certificazione.

Il Certificate Transparency Log è un registro pubblico e immutabile di tutti i certificati emessi da una Certification Authority (CA). Questo registro fornisce un meccanismo trasparente per monitorare e verificare l’emissione dei certificati, consentendo di individuare e mitigare potenziali minacce alla sicurezza, come l’emissione di certificati fraudolenti.

Il funzionamento del Certificate Transparency Log può essere riassunto nei seguenti passaggi:

- Richiesta di Certificato SSL: Un sito web richiede un certificato SSL a una Certification Authority (CA).

- Emissione del Certificato SSL: La CA emette un certificato SSL.

- Registrazione nel Certificate Transparency Log: Il certificato emesso viene registrato nel Certificate Transparency Log insieme ad altre informazioni pertinenti, come il nome del dominio, la data e l’ora di emissione e altri dettagli.

Nonostante il Certificate Transparency Log sia stato progettato per migliorare la sicurezza e la trasparenza, la sua stessa natura pubblica può comportare rischi di Information Disclosure.

Di fatto, non è una novità che gli attaccanti abusino del Certificate Transparency Log per individuare sotto-domini e ampliare in questo modo la superficie di attacco e, di conseguenza, la possibilità di fare breccia nell’azienda target.

Introduzione a DDNS (Dynamic-DNS)

Dynamic Domain Name System (Dynamic DNS o DDNS) è una tecnologia che consente agli utenti di associare un Fully Qualified Domain Name (FQDN) a un indirizzo IP che può cambiare nel tempo.

Il processo coinvolge due elementi principali: un client DDNS installato sul dispositivo che si desidera rendere accessibile e un server DDNS gestito da un provider di servizi.

Sebbene questo tipo di tecnologia non sia consigliata per l’uso in ambienti SMB (Small and Medium Business) o Enterprise, è molto popolare in ambienti SOHO (Small Office/Home Office). Infatti, un numero crescente di fornitori sta integrando questo servizio nelle proprie appliance.

Mass-Exploitation

L’ultilizzo combinato delle due tecnologie, ovvero richiedere un certificato SSL per un FQDN associato a un dominio DDNS di un determinato vendor, può creare un problema relativo allo sfruttamento massivo di vulnerabilità.

Si pensi ad esempio a un produttore di firewall “ACME Inc.” che offra il suo servizio DDNS sul dominio “acme-firewall.com”.

In caso di vulnerabilità su questo firewall, un attaccante può sfruttare il log della Certificate Transparency per individuare target vulnerabili semplicemente cercando tutti i sotto-domini di “acme-firewall.com” e compromettere massivamente migliaia di dispositivi esposti.

Fortinet

FortiNet nei prodotti firewall FortiGate, ha introdotto il servizio “FortiGuard DDNS” che, oltre ad agevolare il setup di sistemi VPN in assenza di IP statico, di fatto incoraggia l’esposizione ad internet dell’interfaccia amministrativa dell’appliance.

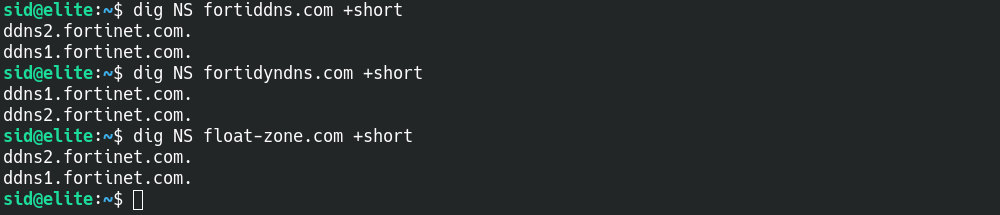

Il servizio FortiGuard DDNS utilizza tre domini di proprietà di FortiNet: fortiddns.com, fortidyndns.com, float-zone.com, e integra un client ACME per la generazione automatica dei certificati SSL tramite Let’s Encrypt.

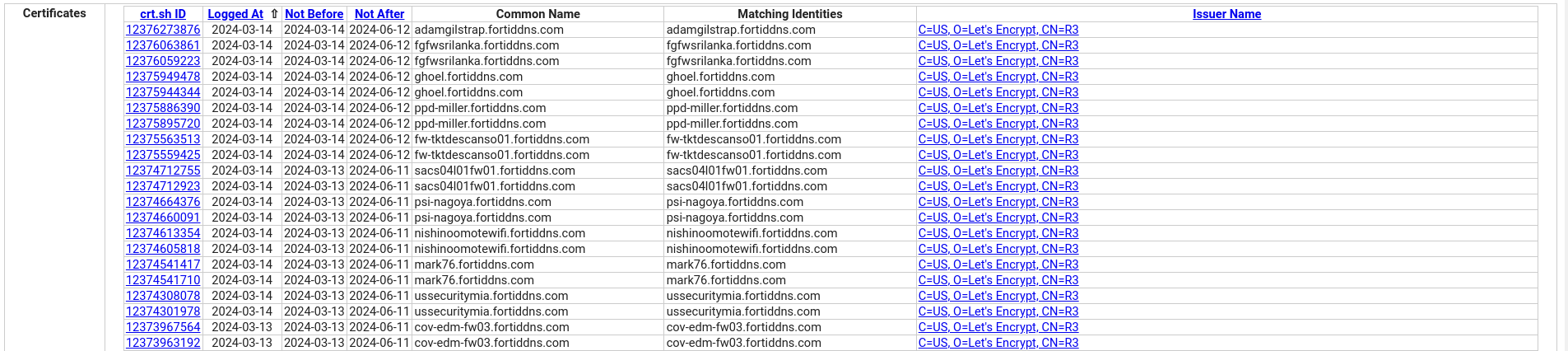

Interrogando un servizio di Certificate Transparency Log per il dominio fortiddns.com un attaccante può venire a conoscenza di oltre 2300 potenziali target a cui è stato rilasciato di recente un certificato per fortiddns.com (risultati filtrati per certificati non ancora scaduti). Il servizio usato per questo esempio ha troncato i risultati per la presenza di troppe entry corrispondenti alla query di ricerca, questo significa che in realtà i potenziali target sono molti di più.

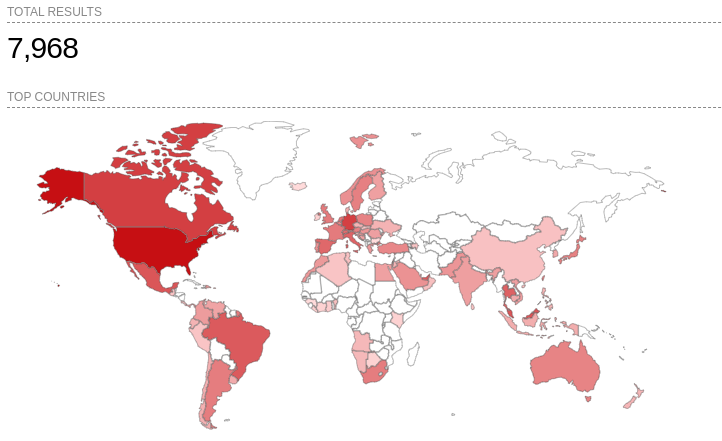

Su Shodan invece sono indicizzati ben 7968 target per lo stesso dominio. La quasi totalità degli host è stata indicizzata tramite il campo “Common Name” del certificato SSL.

QNAP

QNAP dispone del servizio “myQNAPcloud” per semplificare l’accesso remoto ai propri prodotti NAS.

Anche in questo caso, il produttore incoraggia di fatto l’esposizione ad internet dell’appliance tramite tale servizio che utilizza il DDNS proprietario myqnapcloud.com.

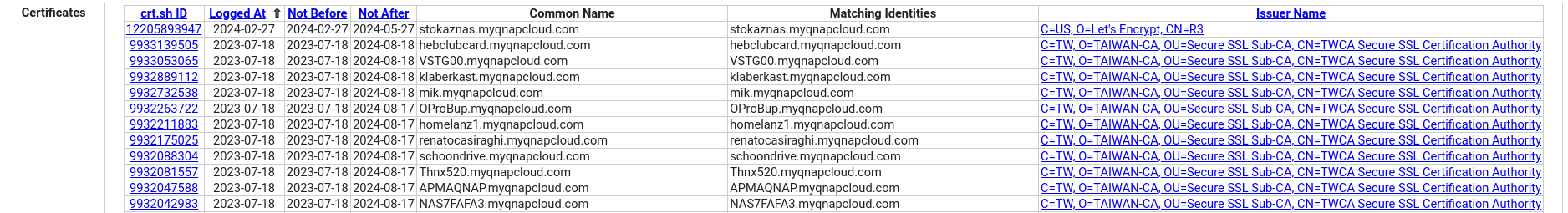

Il servizio di Certificate Transparency Log interrogato restituisce oltre 4400 potenziali target, anche in questo caso i risultati di ricerca sono troncati.

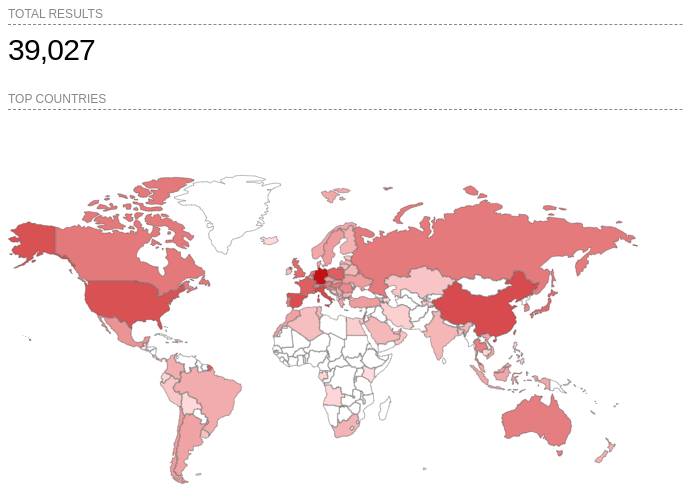

Shodan restituisce 39027 target, anche in questo caso indicizzati tramite il campo “Common Name” del certificato SSL.

Mikrotik

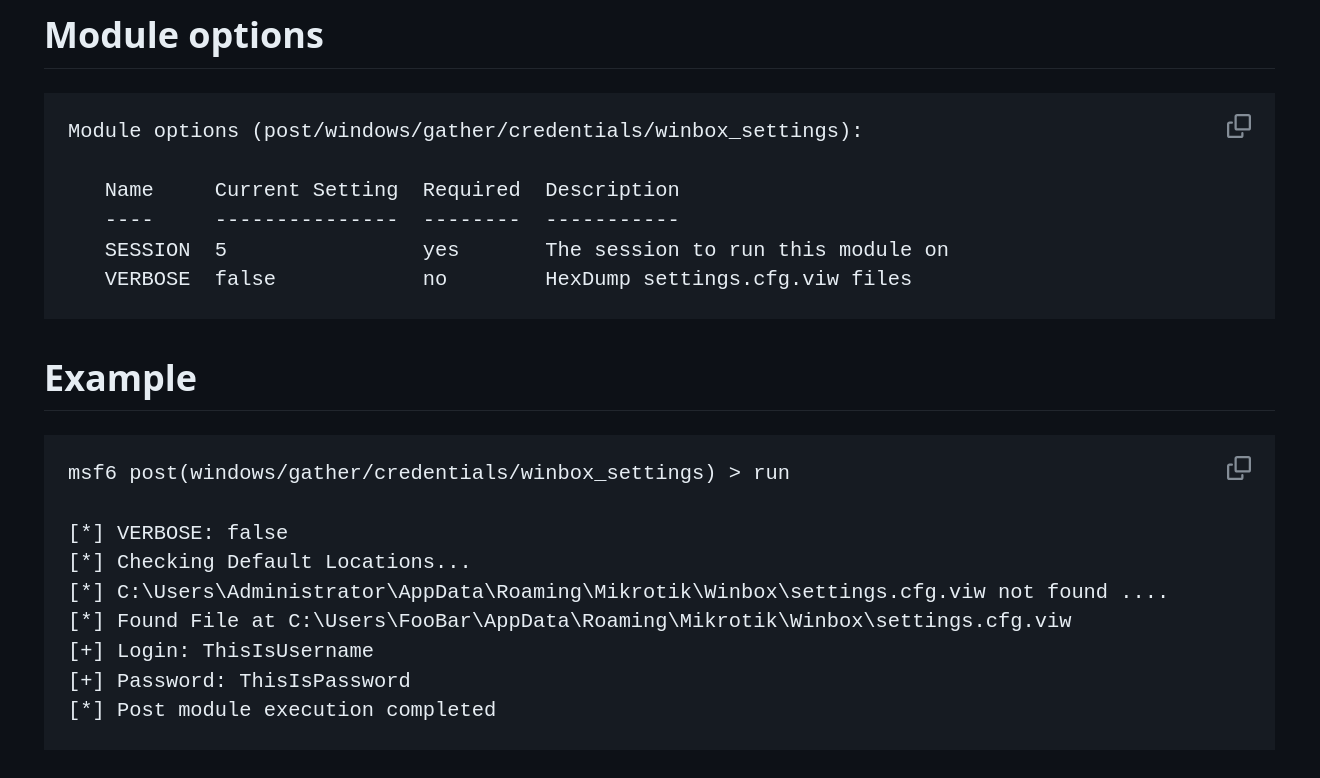

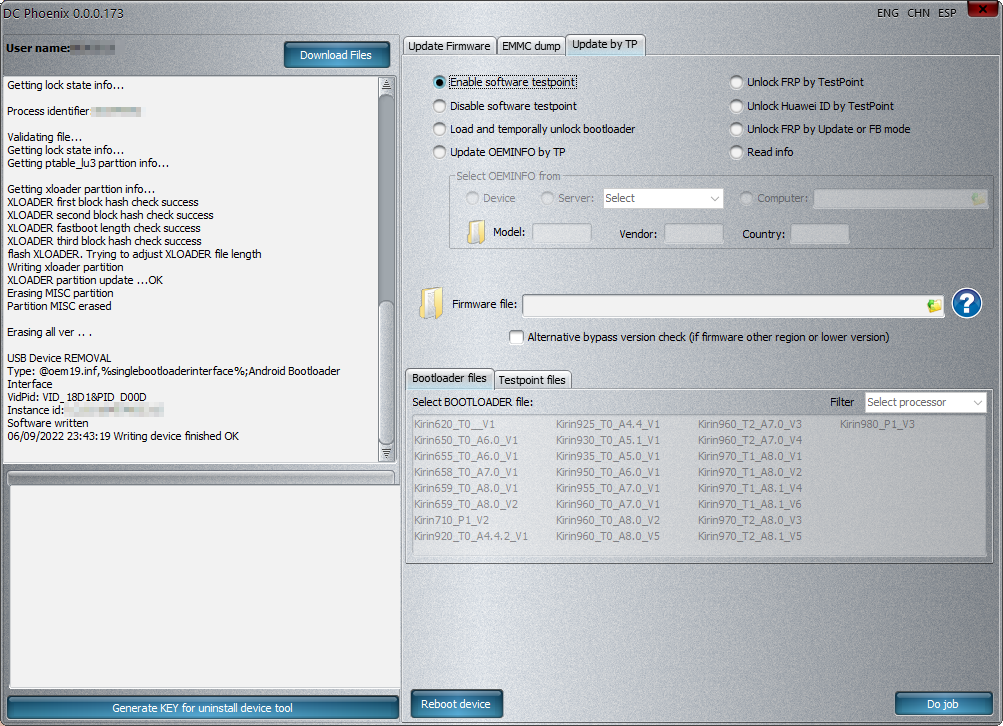

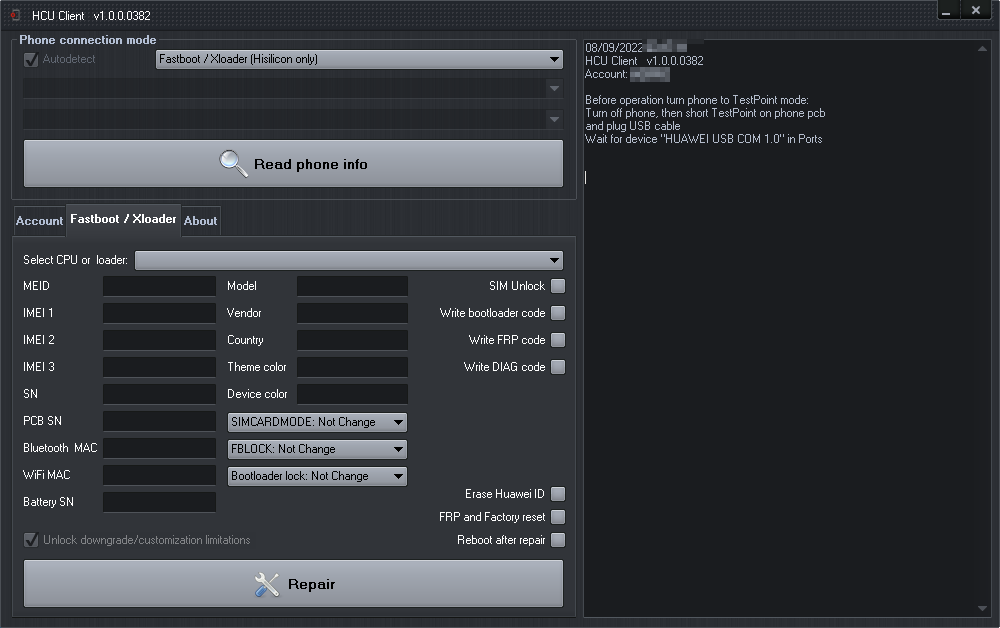

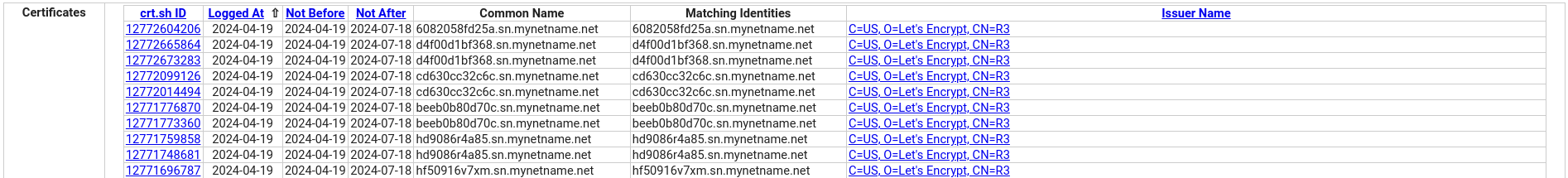

Anche Mikrotik, produttore di router e switch, dispone di un servizio DDNS sul dominio sn.mynetname.net e integra un client ACME sulle loro appliance.

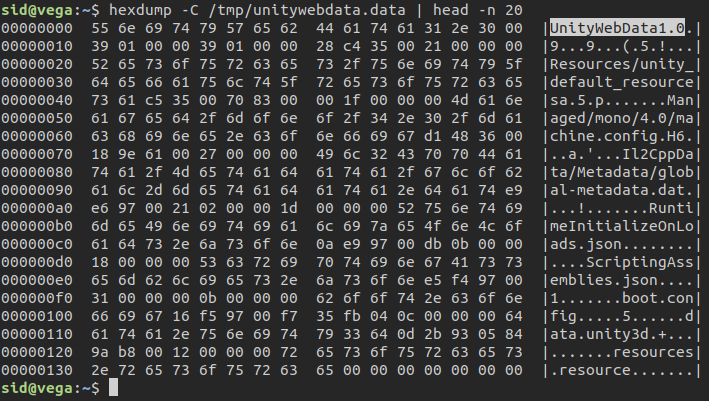

Il sotto-dominio generato dal servizio è composto dal numero seriale dell’appliance (che corrisponde al MAC address della prima interfaccia di rete), esempio: serialnumber.sn.mynetname.net.

L’FQDN generato dal servizio è composto dal numero seriale dell’appliance (che corrisponde al MAC address della prima interfaccia di rete), esempio: serialnumber.sn.mynetname.net.

Il servizio di Certificate Transparency Log interrogato restituisce oltre 1300 potenziali target, anche in questo caso i risultati di ricerca sono troncati.

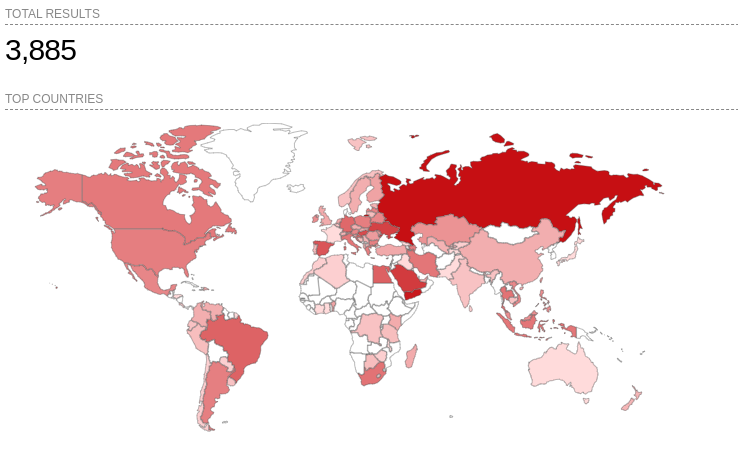

Shodan invece restituisce 3885 target indicizzati per Common Name.

Conclusioni

Anche se l’utilizzo di DDNS non implica automaticamente l’esposizione ad internet di interfacce amministrative e servizi, di fatto ne incoraggia la pratica.

Ad ogni modo, quando utilizzato in concomitanza con un client ACME che genera automaticamente un certificato X.509 sul dominio DDNS, si viene a creare automaticamente un problema di Information Disclosure.

Pertanto, è fondamentale che i produttori comunichino chiaramente agli utenti questi potenziali rischi per la sicurezza, sottolineando l’importanza di una configurazione prudente.