Versione italiana: qui

There was a time, up until the early 2000s, when those who worked in computer security did so because they simply couldn’t help it. Not for the market, not for certifications, not for a career. They did it because they had fallen into a strange world full of curious, often unruly people, all driven by an unstoppable desire to understand how things really worked, and -above all – to share and compare notes.

It was a living, underground ecosystem where every discovery automatically became someone else’s discovery, too. Where the hacker spirit – the real one, built on collaboration and exchange – mattered far more than any job title printed on a business card.

Today, looking at what the industry has become, that spirit seems to have evaporated.

Not because competent people are lacking, quite the opposite.

The generational shift brings into corporate cyber teams professionals with academic backgrounds, master’s degrees, certifications, and sparkling LinkedIn CVs. But something is missing. That sense of community, of “us against the complexity of the world”, which once held everything together, is gone.

And when that spirit is gone, you can tell.

You see it in communities that crumble and then die.

You see it in vendors who treat security reports as nuisances to be minimized rather than opportunities to improve – like what I personally experienced with Tinexta InfoCert’s GoSign Desktop.

A case that (unfortunately) reflects the present

GoSign Desktop is a widely used digital-signature application: public administrations, companies, professionals. Thousands of documents signed every day.

At the beginning of October this year (2025), I found two serious issues in GoSign Desktop (versions ≤ 2.4.0):

- TLS verification was disabled when using a proxy (very common in enterprise environments);

- the update mechanism relied on an unsigned manifest.

In practice, anyone capable of performing a MitM attack could:

- intercept and read traffic;

- provide a fake manifest with a malicious update;

- execute arbitrary code on the victim’s machine:

- on Windows and macOS with user privileges;

- on Linux with root privileges.

Additionally, on Linux there was another Local Privilege Escalation scenario exploitable regardless of GoSign’s proxy settings.

A disaster waiting to happen.

Link to the official disclosure.

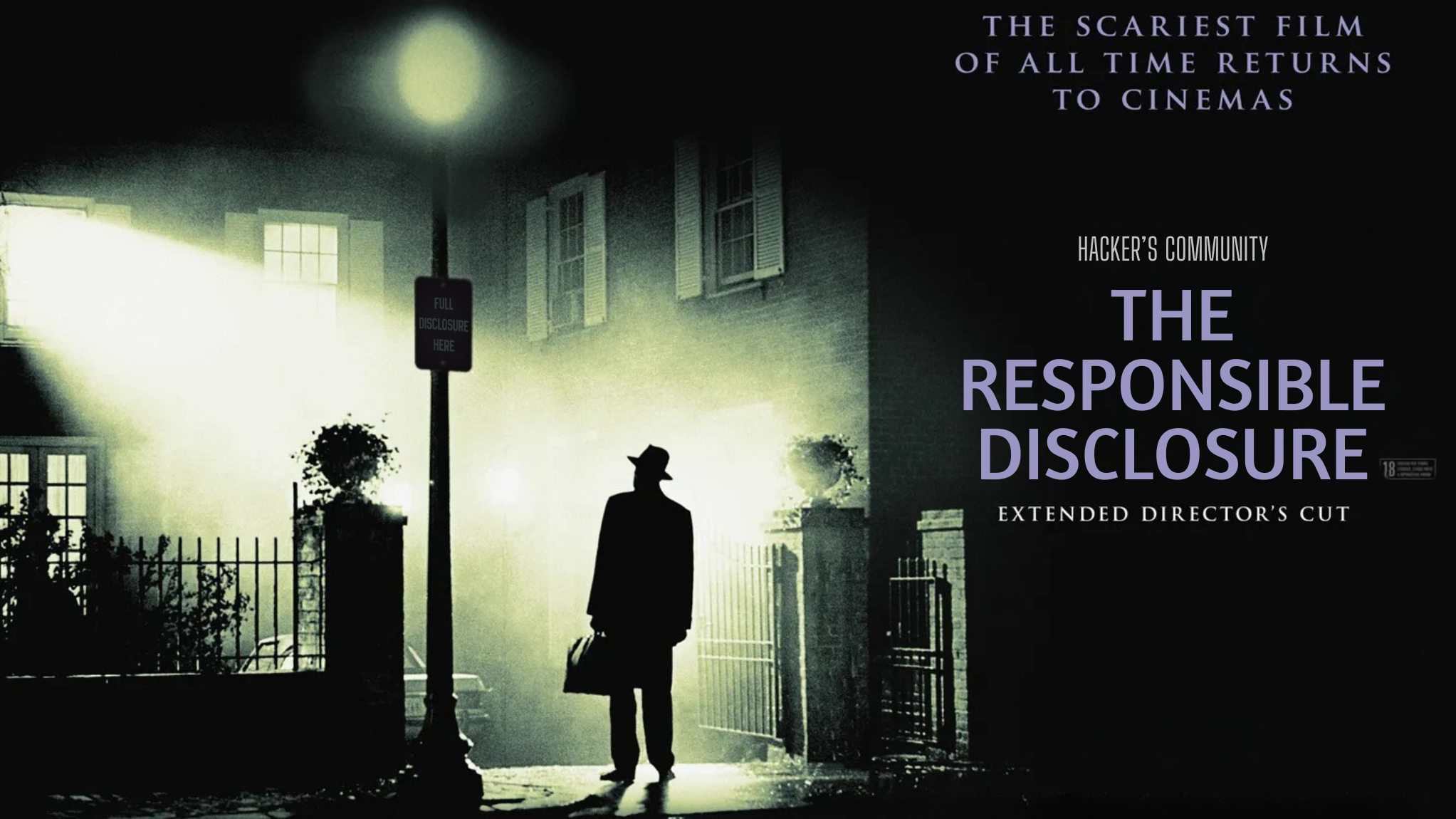

Responsible Disclosure (one-way)

I did what any serious researcher does: I reported the vulnerability to the vendor, shared details, PoCs, mitigations. I made myself available for a technical call on October 16th, where the security lead and product owner confirmed everything. Together we agreed on a patch deadline at the end of the month.

I didn’t ask for money; if anything, a mention in the ChangeLog – as is customary -would have been appreciated.

Anyway, I was waiting for them to notify me once the patch was ready, so I could publish the advisory with no risk to users.

And this is where the story stops.

Or rather: Tinexta Infocert S.p.A. stopped.

After that call, during which I shared all technical details pro bono, silence. No updates. No email replies. No discussion.

Then, on November 4th, version 2.4.1 was released. I noticed a few days later. A version that quietly included the very fix I had proposed – published silently, without any notice, without any acknowledgment, without recognizing the work of the person who found the issue, without even a message saying “okay, it’s out”.

Calling this mishandling “inappropriate” is an understatement.

It perfectly illustrates the state of the industry.

Why?

Because in a healthy environment – one based on mutual trust – a vendor would be grateful. They would collaborate. Engage. Acknowledge.

Instead, today security feels like just another piece of the product lifecycle: something to wrap up quickly, minimize, hush.

ACN/CSIRT Italy (the Italian National Cybersecurity Agency) has been informed about both the vulnerability and the vendor’s improper behavior. And that was the right thing to do.

Beyond GoSign

This story isn’t interesting only because of the vulnerabilities – serious ones – or the poorly handled disclosure.

It’s interesting because it’s symbolic. It’s an example of what’s left when the hacker spirit disappears: a cold, corporate world with no empathy, where someone reporting an issue – donating their skills for free – is seen as a reputational risk rather than an ally.

And it’s paradoxical, because security – and in this case even a bit of national security – depends precisely on those who still have that mindset: independent, curious people who dedicate their free time and expertise to checking what no one else checks. People who do pro bono research, without structures, without budgets, without product management teams.

People who do it because they believe that if something is broken, the right thing to do is to report it, for everyone’s benefit.

What We Lost

We’ve lost our sense of collective responsibility.

We’ve lost the ability to speak openly.

We’ve lost the idea that security is a common good, not a commercial asset to be locked behind a wall of NDAs.

And when the industry fills up with top-down professionals, trained more in academia than in the mud of real communities, this happens: we become excellent at threat modeling and incapable of talking to someone who’s trying to help.

Because empathy is missing.

The culture of exchange is missing.

The spirit is missing.

Cybersecurity is no longer a hacker’s game. And that’s a problem.

Because without hackers- the real ones, not the cartoon villains in corporate slides – what’s left is a sector full of rules, procedures, KPIs… and massive gaps. Gaps and holes no one sees.